Baek Eunsook’s lungs began to burn. Her bones felt as though they were being crushed. She needed to reserve enough oxygen to guarantee a safe, slow ascent. Should she risk a few more seconds to pry a sea urchin, inches within her grasp?

The difference between gratitude and greed—life and death—can be determined in an instant. Jeju Island’s aging women of the sea in South Korea, known as haenyeo, have a saying: “When we dive into the sea, we think we are carrying the bottom of our coffin.”

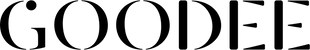

Brenda with one of the Sea Divers.

They view oceans as their working fields. The majority of today’s free divers are over 60. A dying breed, an estimated 4,500 still don rubber suits, goggles, fins, nets with flotation devices without the aid of scuba tanks. “We don’t need them,” said one haenyeo. “They’re too much trouble.” Indeed, one can hold their breath at depths of 65 feet for as long as 1-3 minutes. Such repeated intervals for several hours allow for quite a hefty collection of abalone, conch, octopuses, sea urchins and turban shells.

The first mention of female divers in Korean literature first appeared in a 17th century monograph of Jeju geography. Prior to that, Jeju's diving tradition dates back to 434 A.D. when the activity was exclusively a male profession. I first saw the haenyeo in the mid 1980s. Never before had I seen other Korean women—my size and body shape—diving with gray hair.

Years would pass before I returned to Jeju Island in 2007, 2008 and 2009 as a photojournalist to document the lives of this matrifocal society. My research resulted in the publication of “Moon Tides—Jeju Island Grannies of the Sea” in 2011.

At that time, I learned to appreciate their communal sense of responsibility to each other, their families and villages. Whenever they dive, they work in groups. Each diving community has their own association and strict protocols for harvesting marine products. Many offspring have been sent off to college based on their mother’s earnings—the most productive earning as much as $25,000 per year.

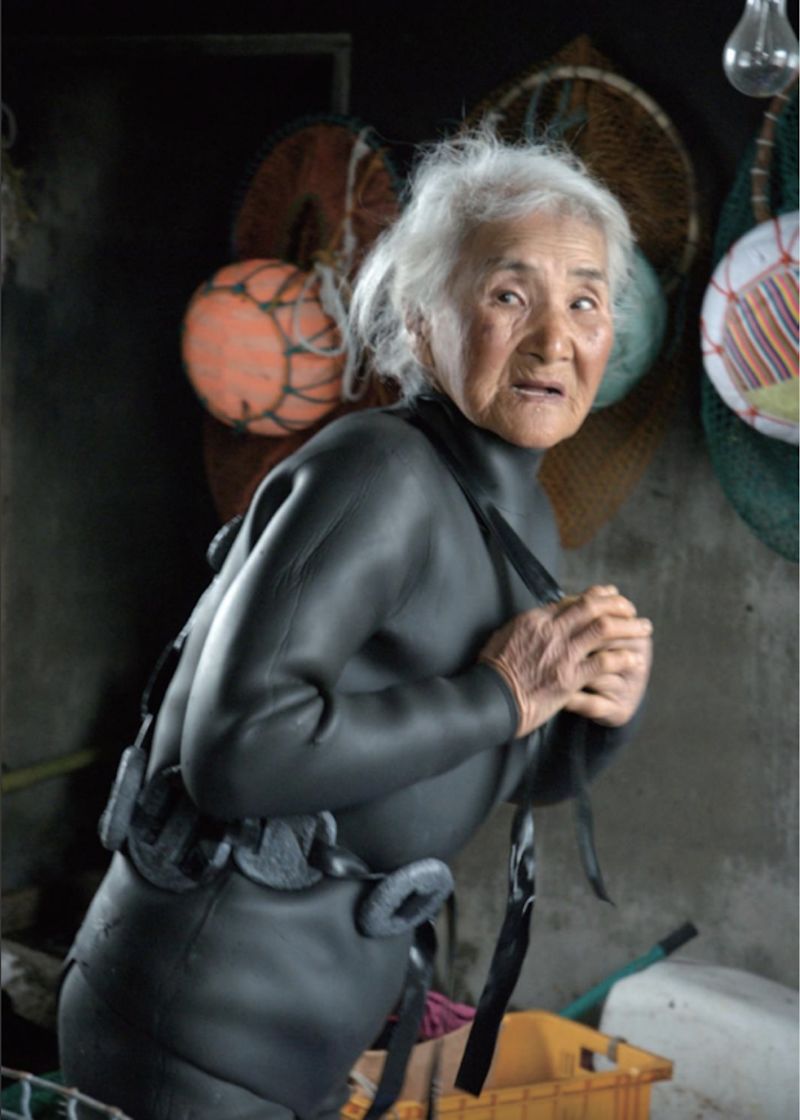

Woo Sun-deok post diving session rinsing her suit.

Most haenyeo I interviewed said they learned to dive by following their mothers to the sea before age 10. They were taught not only how to scour the ocean floor, but to respect the underwater source of food for their families. “I am careful not to be too greedy because there are fewer sea products than five years ago, said Woo Sun-deok in 2007. Warmer climate and polluted waters also are factors reducing their abundance.

Safety is a predominant concern. During the springtime, the haenyeo attend charismatic shaman rites to pray for their protection and successful harvest. “The guts are important because they risk their lives all the time in the water. They need something to rely on. The guts give them security and make them feel at ease,” said Jeju shaman, Suh Sun-sil.

Nearly 15 years later, I’ve acquired a deeper appreciation for these sea stewards. Jeju haenyeo have always been inseparable from the global human chain of Planet Earth environmentalists. This windy island of nearly 700,000 inhabitants is part of the Pacific Ocean—the most polluted of all five oceans. An estimated 2 trillion pieces of plastic are floating underwater, often being mistaken and eaten by sea turtles and other fish. Dead zones are increasing. Halfway between California and Hawaii is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Jeju Island shares the burden of these crises.

As part of their civic responsibility, younger haenyeo regularly dive into the sea to extract garbage: plastics, fishing nets, bottles, cans, oyster traps, styrofoam and other human litter. Tourism, overdevelopment, a naval base and plans for a second airport also threaten their survival. In pre-Covid years, Seoul-Jeju consistently ranked as the world’s busiest air route, with an average of nearly 200 flights per day. Unfazed by the attention of tourists and the media for their prowess, haenyeo view themselves simply as ordinary workers.

Their propitious legacy is best summed up by oceanographer Sylvia A. Earle: “If we fail to take care of the ocean, nothing else matters. No ocean. No us. We need to protect the ocean the same way we protect the land. The ocean is the galaxy of life.”

Discover Brenda's book Moon Tides here.

Image courtesy of Moon Tides.