Better Living

Down to Earth

From lunar colonies to global villages.

Words by Eve Thomas

Images courtesy of CalEarth

CalEarth SuperAdobe at the Junoot Eco Resort in Oman, awarded the World Architecture Award in 2012. Image c/o CalEarth.

How do you build a home on the Moon?

In 1984, NASA put out a call for prototypes of lunar and martian colonies. Iranian-born architect Nader Khalili responded with what would eventually become SuperAdobe: a patented system of stacked, coiled bags filled with earth (or sand, or moon dust), held together using barbed wire and transformed into his now-signature “eco-domes.”

CalEarth creator and architect Nader Khalili looking into a SuperAdobe. Image courtesy of CalEarth.

Despite these outer space origins, it was the issues closer to home – refugee camps, climate change, housing insecurity – that inspired Khalili to pivot from designing skyscrapers to founding a non-profit, the California Institute for Earth Architecture, in 1991.

Like the domes themselves, CalEarth’s vision is deceptively simple: “a world in which every person is empowered to build a safe and sustainable home with their own hands, using the earth under their feet.”

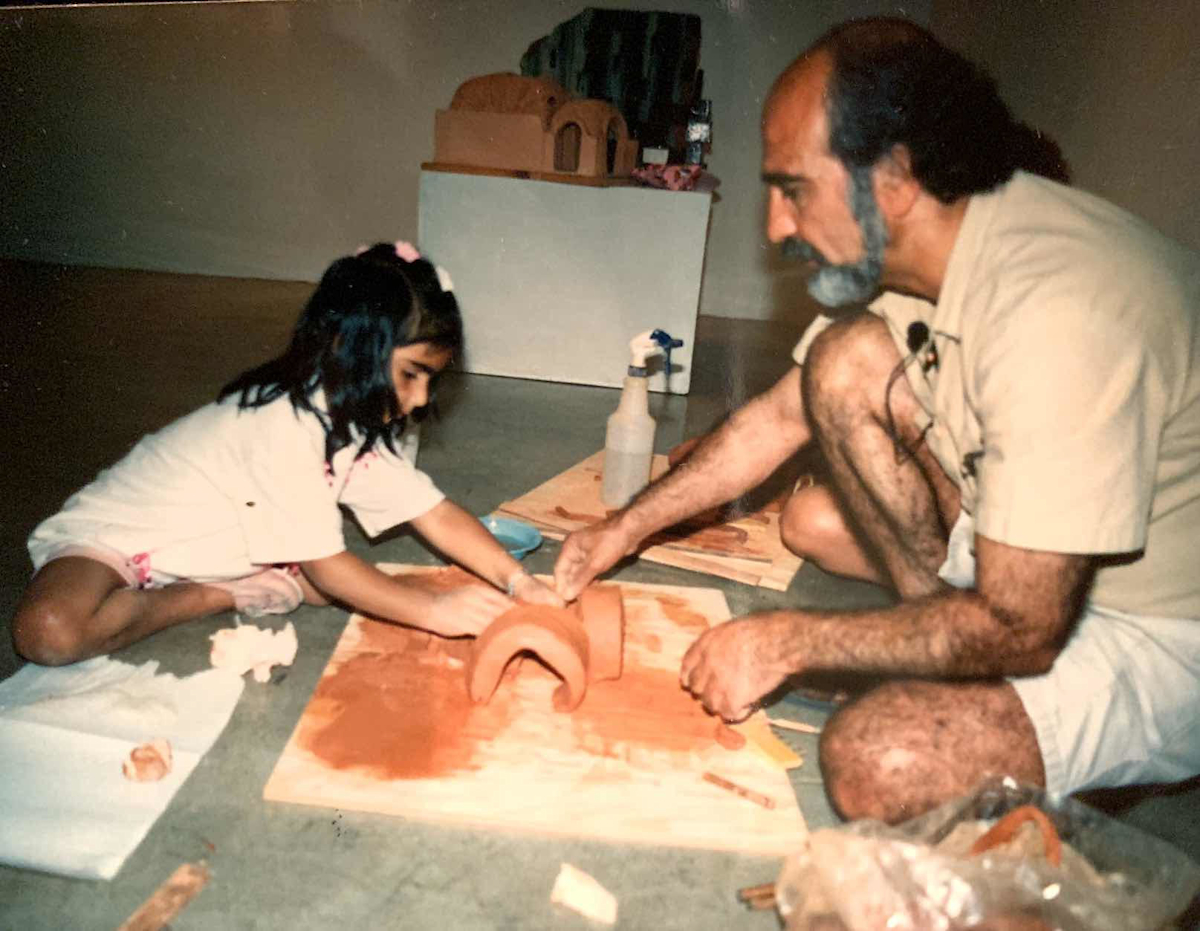

CalEarth creator Nader and his daughter Sheefteh as a child building models from clay. Image courtesy of CalEarth.

Nader’s daughter Sheefteh saw the scale of the problem firsthand while visiting Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. “Families were in tents, with sheeting, metal, thrown together,” she recalls. “In these situations, temporary shelter becomes semi-permanent housing, and most designs aren’t meant for that.”

While she was sure CalEarth could be part of the solution, she also knew that the how was as important as the what.

“My father wanted to empower the individual, and he was always looking to simplify,” says Sheefteh, who took over CalEarth with her brother Dastan after Khalili passed in 2008. While she was on campus four to five days a week early on, her goal was always to step away from day-to-day operations and admin (she also works at a nearby university and lives in Orange County), instead focusing on the organization’s broader goals and events like open houses.

Left: Builders filling the bags that create the outer dome structure. Right: The 'Coffee Can' technique which allows the bags to be filled in place one coffee can at a time, making it simpler for any one to build their own home. Images courtesy of CalEarth.

This overarching goal for simplicity is apparent in the organization’s “coffee can technique.” Basically, the structures’ bags are filled in place, already on the wall, with no heavy lifting or expensive tools. So, whatever a person’s age, gender, or level of skill, if they can carry one can of organic material in a coffee can or whatever vessel they have on hand, they can fully take part in building their own home.

“There is a sense of spirituality here – and I don’t mean religious – a connectedness. You can sit and take a deep breath and be present, there is a stillness and a beauty in these earth homes."

This vital sense of ownership – and place – comes alive in eco-domes in over 50 countries around the world, from Djibouti to Japan, Canada to Sierra Leone. Each modular structure is not only adapted for its climate but reflects its makers’ cultures and crafting techniques, through brightly painted pallet doorways and mosaics made from recycled bottles.

CalEarth’s global reach has been boosted in large part by putting the entire curriculum online, a longtime dream of Khalili (“He died before the iPhone came out, but he had a vision even before the technology was there.”) It doesn’t hurt that the domes are inherently Instagrammable, have been featured in shows like House Hunters, or turned into eco-retreats in places like Acapulco and Ecuador.

A SuperAdobe interior eating nook. Image courtesy of CalEarth.

At the same time, the California campus remains an essential site of hands-on experimentation and inspiration. Visitors can tour the Rumi Dome, inspired by Khalili’s favourite Persian poet, where light comes in from all sides and Sheefteh herself goes to find calm and recall her father’s lectures; they can check out the construction of an underground “bunker” dome; and they can learn about the new Duffel Bag dome, which fits the tools and materials for a six-foot emergency shelter into two bags that can be checked as luggage. The idea is for trained teachers to quickly fly to a community in need, build the structure with locals, then leave them with the ability to build more themselves using accessible materials. “Barbed wire, sandbags, what my dad called the materials of war.”

Sheefteh has noticed a shift in who’s on campus, too. Rather than people already living alternative lifestyles (i.e. hippies), more millennial couples are interested in building their own homes. Buoyed, perhaps, by the aesthetics and eco-friendliness of the tiny house movement, they’ve also lived through earthquakes and wildfires, as well as mounting debt. The temptation of a mortgage-free home – albeit one that can be designed to include three bedrooms and a two-car garage – may be enough to make a generation see the benefits of living with less.

And this is great news, says Sheefteh. “The intention was never to be on the fringes or off the grid.”

Nader and Sheefteh as a child in front of an adobe construction. Image courtesy of CalEarth.

Whoever they are and wherever they come from, most visitors have one thing in common: the way the CalEarth campus makes them feel.

“Thousands of people have told us, ‘I’ve never been here before, but it feels so familiar, so calm,’” says Sheefteh. “There is a sense of spirituality here – and I don’t mean religious – a connectedness. You can sit and take a deep breath and be present, there is a stillness and a beauty in these earth homes. My father called architecture ‘tangible poetry,’ and he built in harmony with nature. It’s something beyond construction. It’s something more.”

Editor's Note: The opportunity to visit CalEarth is changing day to day due to Covid-19 but is currently happening. Please visit CalEarth site for more info.

About Eve Thomas

Eve Thomas is a Montreal-based journalist, writer, editor and marketing expert with over 10 years of experience creating print magazines from scratch and developing online content people actually want to read. She does a bit of everything, with a focus on luxury travel, corporate profiles and lifestyle features.