I’m sitting on the floor of my parents’ living room in Texas, where I’ve unexpectedly been quarantining since this second wave of COVID-19, when I speak with Chad Berry over Zoom. He has offered to tell me more about Berea College, for which he is Vice President for Alumni and College Relations. After I sort out the inevitable technical difficulties, I share that I didn’t attend an American university myself, instead studied and then continued to live in Paris until recently. He jokes about wishing this interview could be conducted at a terrace café somewhere rive gauche. Seems we are both a little nostalgic for a not so distant past, when travel and in-person interviews were still a thing.

However, on the other side of my screen, Berry finds himself in Kentucky, at the heart of Appalachia. Which makes it all the more astounding to learn of Berea’s founding story, being the first interracial and coeducational school established in 1855, by Reverend John Gregg Fee, in what was still the slave-holding South. The reverend and his wife began classes in a one room church built on land gifted to them by the renowned abolitionist Cassius Clay. “Rare is a vision as distinctive and relevant 150 years later”, Berry notes, as he assures me that the audacity and courage of Fee’s initial vision continue to guide Berea’s progressive philosophy in 2020. Berea College is still committed to “radical inclusion” and “educational opportunity” (this is plainly stated in the school’s Great Commitments). This by ensuring ethnic and gender diversity of course, but also perhaps something even more renegade by 21st century American standards: offering a tuition free education.

Berea College in Kentucky, USA.

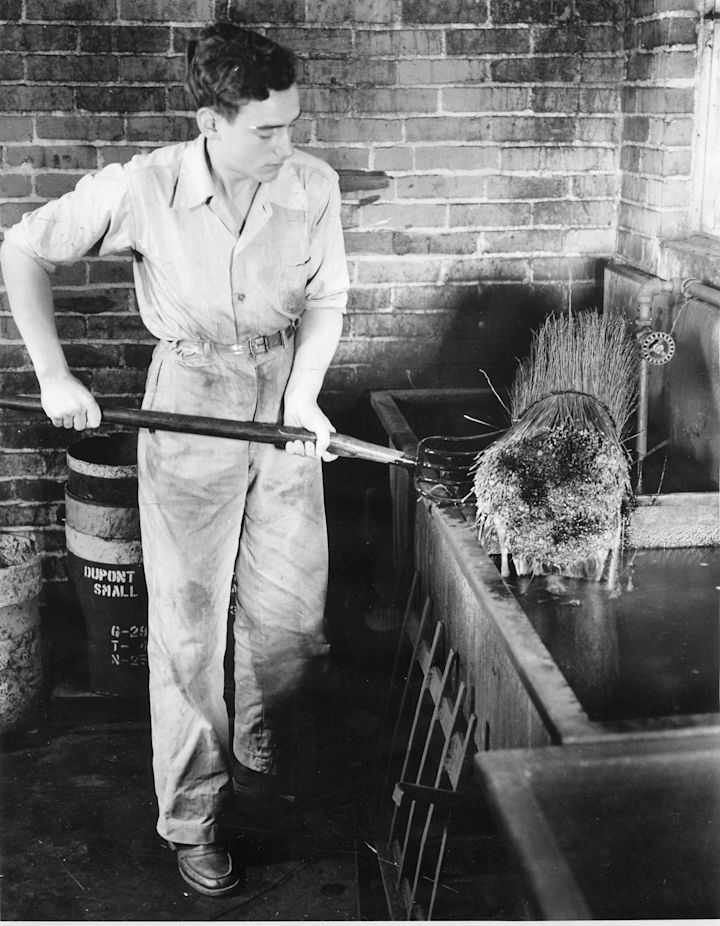

In an age where student debt has entered the stage of “crisis”, it’s remarkable to learn that Berea’s endowment covers 73% of its operations – the rest comes from annual fundraising and grants – while, at full capacity, educating as many as 1660 students. In fact, Berea’s endowment celebrated its centennial this year. This self-sustaining financial model echoes a focus on everyday sustainability on the campus as well. The college has made green initiatives in student housing and runs a farm which provides some of the food served on campus, as well as supplying the raw materials for the student workshops. Said workshops are part of what sets Berea College apart: all students here are expected to have an on-campus job.

Our conversation leads me to understand that this cooperative system is as

pragmatic as it is philosophical. “Dignity in labor” says the website. In this work-study model, students might serve

lunches, or weave brooms all while they pursue a liberal arts degree. While

this likely keeps operational costs down, it is seen as adding a third “hand”

dimension to “head and heart learning”, as Chad puts it. The college’s

long-standing crafts program in particular offers an opportunity for both

experienced and novice students to explore working with their hands and develop

an additional skill.

I was fortunate enough to speak to a student who has joined the broom workshop, which is also celebrating its 100th year. Victoria speaks to me from her dorm room, where the motion-sensitive energy-efficient lights flick off from time to time. She’s a 22 years old junior with a double major in Studio Art and Art History. Confident, sincere and enthusiastic, Victoria is from New York state, outside of Buffalo, and she tells me her great-grandmother was a Berea alumnus. When I ask about her first impressions of the workshop, she mentions the distinct sweet odor of sorghum and the camaraderie. At the college, students are expected to work 10-15 hours a week, but it doesn’t appear to be such a chore, as she puts it “it gives your mind a break”. This past semester, under the supervision of Chris, “the head broom dude”, and his apprentice, Victoria has been learning the different stages of broom-making. Here a dozen varieties are assembled by hand; handles are made from reclaimed furniture and local walnuts and osage are used to make some of the dyes.

A recent collaboration with designer Stephen Burks, coined “Crafting Diversity”, gave birth to new ideas and products in these time-tested workshops. Burks was the first person of color to hold a leadership position in the school’s crafts program and with a “wealth of knowledge and tradition to build upon” pushed to expand its horizons in all of the various practices. Burks, along with the students, even looked beyond the practical and explored the sculptural dimensions of broom craft for example, with a decorative piece being added to their broom catalogue. Although she’s a painter, Victoria tells me she doesn’t adhere to any hierarchy of the Arts and feels the same pride in a well-made broom as she would a canvas.

Designer Stephen Burks guides students through the design process of producing contemporary pieces from age-old techniques.

“Tradition, diversity and change, work together in creative tension” says Chad Berry, providing what he calls the kinesis which sustains this school’s atypical model and pushes it steadily into the future. It is a model he hopes will inspire other schools. It seems clear to me there is a growing need for educational alternatives – and in particular ones that do not burden students with unmanageable debt – having observed a shift in expectations amongst Americans, in particular its college-aged youth. Until then, Berea continues to “challenge people’s conception of what an affordable education looks like”, mine included.